Here is a short story from my experimental memoir, written years ago.

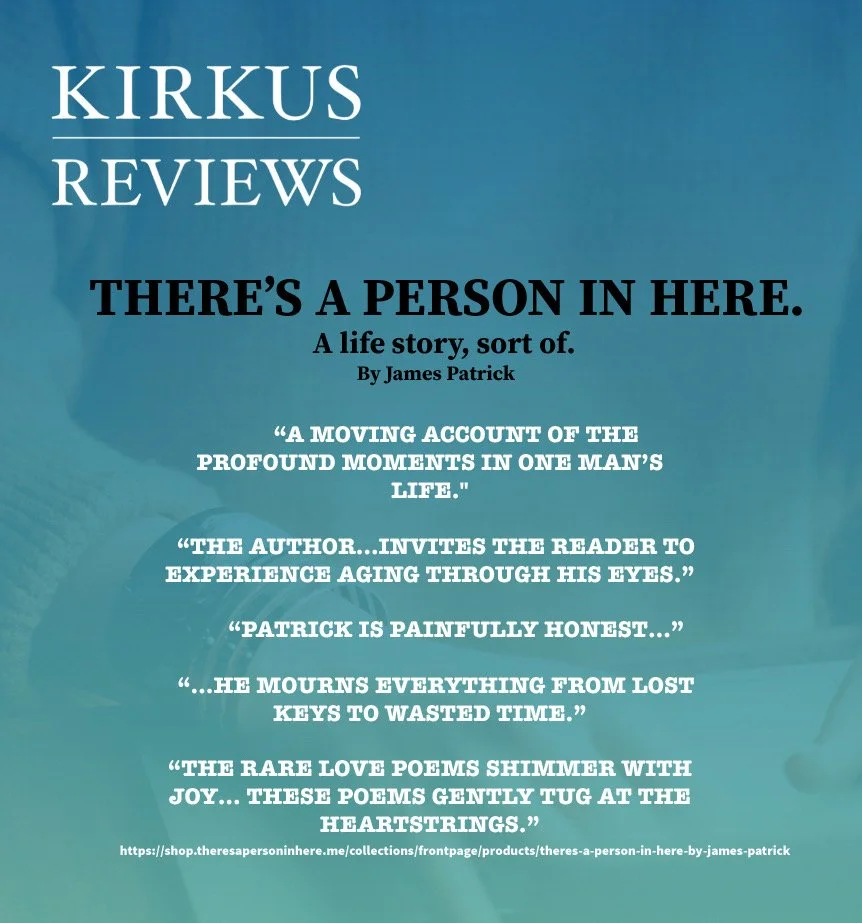

Full KIRKUS REVIEW:

A Eulogy.

All he could hear on the way up to the podium was the clicking sound of his heels against the cold marble floor of the church. Loud, cold clicks that he associated with the heartbeat of the man he was and the father he was to eulogize.

The phone rang Sunday afternoon, December, 5th , and when he answered it he heard his brother tell him that their father had expired and that someone had to go to the hospital to make arrangements for the body to be removed and sent to a funeral home. His family was at the kitchen table, but he did not remember talking to them, not even talking to his soon-to-be ex-wife who would react very poorly to the demise of the patriarchal figure in her life.

He slowly went out the backdoor and got into his car, the same car he would catch his wife riding in with her tennis instructor/lover, and drove to the hospital.

He was familiar with the route. He estimated that he had made this 1.1 mile trip at least 250 times over the past four years. First to visit his father. Then his mother. Then his father again. With a few uncounted trips to see his aging grandmother before she checked in to the Sunny Way Nursing Home in order to recuperate from the stroke, it was easily over two-fifty.

He pulled into the same hospital parking lot that he had pulled into eighteen years before to be present at the birth of his first daughter.

He walked in the backdoor of the hospital as if he were an employee returning to work. He knew the way to his father’s deathbed like the back of his hand. Up the elevator, to the right, around the nurses station on the left, three doors past the smell of urine, and forty years into the past.

No problem until he got to the door of his dead dad’s room. It was a double room. The heads of the beds were against the left-side wall. The bed closest to the door was empty, with the sheets removed, exposing an unused mattress. The curtain was pulled back, and on the bed table he could see a bedpan and water pitcher. The buzzer hung lifeless over the edge of the bedrail.

The curtain of the far bed, which had been home for his father for the last several weeks was pulled, shutting out his view of the body. He glanced around the hall but did not see anyone he could stall with, so he stared at the curtain and tried to look through it, to see slowly what he knew he would see all at once. He moved into the room up to the curtain, and as his angle changed he saw toes and the bottom of his father’s legs through a space between the curtain and the wall. Soon he could take in his father’s entire dead body.

He was nude on the bed, his eyes and mouth wide open, and he seemed to be gasping for air. But he was still. It was more an outline, really. Like a pencil sketch of a landscape curved across the horizon, distant rolling hills past an open mouth in a head tilted back ever so slightly so that his chin appeared like a bluff over the range of his chest, gray with tumbleweed, resting near the boney crevices of his legs, which pointed straight down to toenails that stood sharp and ragged, splintered from the elements. He would find himself compelled to sketch this view as a single line on a white sheet of paper or on a napkin at a bar or in a meeting or in the sand while at the beach with his children on a happy summer day.

The voice from the podium began, and it sounded strong and sincere. Like it was supposed to. A loving, thankful voice. Firm with manliness. Anger loyally repressed: My father was like many men, a complicated man like many men, he was a strong family man like many men, who loved his wife and children … Like many men … Which is why my brothers and I are here … Like many men today … In remembrance of our father … Like many fathers …

He looked through the casket in front of the altar and X-rayed the outlined relief of the body inside and wondered about the inner landscape of the man before him. Who was it in there? How had this man felt when he was alone? What were his memories of the life they shared, and how could he have been such an enigma? What did he remember? Did he remember the last time they spoke?

It was in the hospital, about a week ago, the culmination of five years of sickness, weakness, and transfusions brought on by a form of leukemia contracted, they believed, as a result of entering Nagasaki as a Second Division Marine, forty-five days after the bomb was dropped. His father’s lungs were filling up with his own white blood cells, erroneously fighting an infection that was not there. In a sense, through a misunderstanding, he killed himself. Very true, only he had started killing himself forty years earlier.

His father was still and very thin. This huge man of his youth was fragile and frightened. His father’s blue eyes called to his son. Shot right through him. Tell me, they said. Tell me, do something, help me, you must help me. The son could do nothing for him. He just denied what he needed to, waiting for his father to get up from bed, clear his throat, and walk to the window to smoke a cigarette and pull out a single to play liar’s poker. This did not happen. His father only kept looking up. Longing. Waiting for one of his three sons to say or do something, to fix things. No one did anything, yet.

The eldest son looked directly down into his father’s sick blue eyes. He could reach out to touch him but instead held the bedrail. Their eyes were less than two feet apart, but it felt like fifty years. The father was sixty-three; the son was thirty-seven, but a part of him felt as if he were still nine. Nine years old. He was nine when he learned, taught himself really, to hate his father, to fear him, to reject him for most of what he was and to stop admitting he loved him for all he was and was not. Nine, when he buried that part of himself that loved and needed him. Worshipped him. The thirty-seven-year-old son stood inches away from his sixty-three-year-old father and was lost in the confusion of a distant nine-year-olds perception of an out-of-control, alcoholic, promiscuous, angry, tormented and loving dad.

It was, the son would learn later, just a misunderstanding.

The father was sixty-three and dying. The son was still nine. It was December. Cold outside. The hospital room was warm. His father had no shirt on. His neck was long between his head and body. It strained like a chicken’s. In the hall, the doctors had explained all the limited options. He had a day or two at most. They could operate and put a hose into the older man’s lungs and force in medicine that might or might not work. That might or might not add a day or two of life, and pain.

The brothers voted, looking to the eldest for the right vote to cast. They would do nothing. They would let their father die. Back in the room, the father searched and found his thirty-seven-year-old son’s eyes. “Where do we go from here?” he asked in what was left of his marine corporal’s voice. The son was silent, but inside, without hesitation, he screamed, straight to hell.

He saw his own children in the pews listening to him, or not, as he spoke loudly in glorious intonations about their grandfather and his accomplishments, and knew at that moment that he was exactly the same as the man he loved and despised and that he was a corrupted version of a corrupted version of a man and a father and a husband … but he chose to ignore that fact and proceeded with the half-lie that was his eulogy and that was, by then, already the fabric of his own life.

He knew the funeral service was to end two hours later at a cemetery on a hill where the body of his father was to be placed in a crypt next to his mother’s home in the wall of bodies. His mother had been the wife, for forty years, of today’s dead man. The man who loved her beyond his own capacity to understand that love. The man who tortured her with betrayals and adorned her with gifts. The powerful man with the undiagnosed broken heart she had unwillingly left behind just six months ago.

The eulogist rarely visited his mother’s crypt. She was the loving but perpetual child of Mary (ensconced in a nursing home and to die in three months) and William Sr. (deceased following a life of postal service and despair), tolerating sister of William Jr. (deceased age fifty, leaving behind two devoted daughters and a loving wife), grateful and awed niece of Katherine (ensconced in a nursing home and to die in four months), emotionally distant yet remarkably present mother of the eulogist and his brothers, and indulgent grandmother of three grandchildren already born and a fourth she would never meet.

His father struggled until the end. He struggled to survive death. He struggled to survive life. He was a Marine, a tough guy; he was the firstborn older brother, who never cried. He was just another man among millions of men. But the only one who mattered.

He was sunshine and darkness. Good and evil. A man who needed to be loved and did not know it or show it. He was a father to a son. A hero and an enemy. A nightmare in a suit. He was the man the son tried to be so different from, and the man the son needed so much to be like.

Surveying the church, the son, finishing out loud, said: … The one we all admired and emulated … …the limousines are waiting now to take us to the cemetery. Thank you for sharing this day with us.

From: There’s a Person in Here: A Collection of Short Stories and Poems About Holding On, Letting Go, and the Space In-Between by James Patrick

Available on Amazon

WHAT ARE YOU THINKING?